Making Teapots

A teapot is a difficult thing to make well; yet, partly because of

this, and partly, I think, because the teapot is such a deep-rooted,

integral part of our daily lives, few things can give a potter more

satisfaction. But the task bristles with difficulties for the unwary,

and I hope the following points of advice will be helpful.

First of all a teapot needs to be fairly broad. One which is

relatively tall and narrow does not infuse so well nor so quickly.

There will be those who dismiss this belief as a pretty conceit.

Nevertheless, it is my firm opinion. So allow for a generous cross-

sectional area of liquid at the surface when the pot is full. Throw

the body of the pot fairly thinly; a heavy, chunky teapot is unlikely

to be popular. Make sure the base is sufficiently broad for stability.

Nothing is more irritating than a pot which wobbles and tends to

topple over when the cosy is lifted off. Keep the opening at the

top as small as possible compatible with easy filling and cleaning.

If it is too wide, too nearly the diameter of the pot at the shoulder,

a sudden tilt, as if to pour, when the pot is full, will cause the tea

to well out under the lid. Leave a slight thickening at the top of

the wall so that, when the shoulder has been turned over, there is

sufficient clay in which to form the gallery for the lid. I find the

best way to perform this operation is to pinch the clay gently at the

edge of the opening between the first finger of the left hand, below,

and the thumb, held vertically with nail outwards above. The

thumb then bears down into the clay at the edge of the opening and

is aided by a slight squeezing by the finger below. When the

gallery is thus formed, the inside edge should be compressed and

consolidated or it will surely chip. For the same reason be sure the

gallery is reasonably thick.

Next throw the spout and the lid. This is where difficulties

which may be experienced at later stages originate. It requires

imagination and skill to throw these parts separately so that, when

they are merged with the body, the pot becomes a coherent, unified

whole-not a jumble of unrelated components. It is true that, for

instance, one can trim a spout that has been thrown too long; but

only at the expense of altering its diameter at either the tip or the

base, which will upset the proportions of the pot in either case. I

find it best to throw the spout on a thick base. This keeps it in

shape when it is taken from the wheel, and the base is cut off when

the clay has stiffened sufficiently for the spout to be trimmed and

luted to the body. One of the secrets of good pouring is to ensure

that a pressure of liquid is built up in the spout. If this is not the

case, the tea merely wobbles over the end. The spout should

therefore taper and the cross-sectional area of the tip should be less,

though not much less-than the total cross-sectional area of the

holes which will form the strainer.

It is best to throw the lid very slightly larger than the socket

into which it is to fit, to allow for a small amount of turning at the

cheese-hard stage. There is no excuse for badly fitting lids in hand-

made pots. For this reason, I often turn the inside of the gallery

to make sure of a neat angle, although this operation should be

completed as far as possible at the throwing stage. At no time is

the turning tool more potentially a vice than when making a teapot.

If the lid is to have a flange, make sure this is sufficiently deep and

fits the inside of the gallery closely. If this is so the lid will remain

in place when the pot is tilted steeply. If there is not to be a flange,

the lid ought to be seated rather deep in the gallery, and it may be

necessary to resort to the common locking device to ensure that the

lid remains in place. Remember that a lid which fits perfectly

when it and the body of the pot are cheese-hard will be a little on

the loose side when both are dry. This is the condition to aim for,

as the slackness will be taken up by the thickness of the glaze.

A lid with a flange is thrown upside down and the knob turned

out of the thick base or luted on separately afterwards. A lid

without a flange is usually thrown right way up. In either case do

make the knob or handle something worth getting hold of. To

have to squeeze a knob hard to lift the lid-especially when it is

hot-is an abomination. It should be possible to raise it securely

with the lightest grasp. Don't forget the vent in the lid to act as an

air intake when pouring. If you do forget it and the lid is as good

a fit as it should be, the pot won't pour-except out of the lid.

Make this vent fairly generous. A tenth of an inch is hardly too

big: and when you glaze the pot, remove the glaze very thoroughly

from this hole or it will clog in the firing and have to be drilled out.

When the spout is leather-hard (it will dry more quickly than

the pot, so you will have to slow down its drying), cut it from the

base on which it was thrown and trim the lower end with a needle

or a narrow, thin pallet knife, so that it will fit the profile of the pot

when held inclined at the right angle. When this is so it is vital

that the lower edge of the tip of the spout is above the level of the

lid. I have seen many teapots made by potters of high reputation

in which this point was not observed. Yet a person filling a pot

watches the level inside the pot-not the spout-and if the tip is

below the level of the lid, tea will dribble out when the pot is filled.

Holding the spout in its correct position against the wall of the

pot, lightly trace the outline of the base on to the wall with a pointed

instrument. Then, allowing for the thickness of the spout wall, punch

the holes for the strainer. In most pots these are either too few or

too small. One-eighth of an inch is about right for the diameter.

If larger they will not arrest the leaves. If smaller they will

gradually clog in use. The spout ought not to be positioned too

low because, although this will help to create pressure in the spout

when pouring, as mentioned before, the tea leaves will settle and

clog the strainer. A very thin, hollow tube is useful for boring the

holes, but a solid instrument will do. I use a tool which comes in

useful for all kinds of work-a discarded dentist's chisel with the

operating end sawn off and the neck filed to a tapering point.

any case the tool should be wetted and pushed through the clay wall

with a twisting motion and any ragged clay edges thrown up on the

inside severely left alone until dry, when they can be neatly flicked

off and the whole area sponged over.

Next scratch up the area round the strainer where the joint is

to be and rub in some thick slip. Lightly wet the butt end of the

spout and press it firmly home, thoroughly consolidating the joint.

Depending upon the nature of the body and the temperature

employed, spouts will tend to twist clockwise in the firing-the

opposite way to what one would expect. Therefore, to counteract

this, they should be attached to their pots in a position slightly

counter-clockwise of that required in the finished pot. Only

experience can decide the degree of compensation necessary. I so

shape the spout and model it on that it grows smoothly out of the

body of the pot and makes a continuous unbroken line with it. A

friend of mine argues that, since the spout is attached to the pot

and not formed in one piece with it, it should look attached. No

doubt this is logical: but perhaps it is a little too logical. After all,

most of us make our handles grow out of our jugs and mugs; so

why not spouts also. As soon as the spout is in place, the tip can

be finally trimmed and smoothed to shape. The lower edge should

be reasonably sharp to aid clean pouring: but remember that clay

does not take kindly to sharp edges and is easily chipped. Do not

overdo it therefore. If possible arrange for a small overhang on

the lower edge. It will greatly improve pouring. But too much

is very ugly.

The handle of a teapot is very important. Not only must it

fulfil its purpose efficiently and comfortably, but its form and the

area of void its loop encloses must balance the spout. On a

medium sized pot it should be possible to get three fingers

comfortably through the loop, the thumb being above and the fourth

finger below. On a larger pot the loop should be large enough for

four fingers. You will very likely find that, to form a comfortable,

efficient hold, the handle looks wrong on the pot or vice versa, in

which case you may have to re-design the whole thing. This sort

of difficulty is implicit in the nature of design and craftsmanship

and it is no good being afraid of it. Preliminary pencil sketches will

help; but do not allow yourself to become a slave to paper designs.

They militate too much against the freedom and spontaneity the

thrown shape should always have.

Generally speaking, the handle should approximate to a flat

oval in section and should be reasonably broad for a good, comfort-

able grip. If you are going to have an overhead cane or clay

handle, make sure that it does not interfere with the easy removal

of the lid and is so proportioned and attached that the pot handles

easily. The attraction of the overhead handle is no reason or

compensation for inefficiency in the pot as a whole.

The glazing of teapots is not altogether straightforward. I

glaze the inside first by pouring in some glaze and pouring it out

again by way of the spout. Then quickly, while the glaze is still

wet, I put the spout in my mouth (lead glazers take care!) and blow

sharply down it. This removes excess glaze from the strainer holes

where it tends to accumulate and would, on firing, stop them up

altogether. To glaze the outside, I stop the spout with a conical

plug of soft clay and, gripping the pot by expanding my fingers inside

it, I plunge it into the glaze until the level rises to the edge

of the lid opening. I usually have to miss a bit here in order to be

certain that the glaze does not trickle over the rim and down inside

the pot. So the rim has to be touched up afterwards with a brush;

likewise the tip of the spout where the plug of clay has been.

With stoneware teapots, where the danger of warping is

considerable, it is best, to obtain well-fitting lids, to fire the pots

with their lids in place. This means not glazing the gallery and the

underside of the rim of the lid. But with a vitrified body this is of

no account. In order to get a particular glaze effect, most of my

pots are fired in excess of 13500C and in a reducing

atmosphere for much of the time. This, together with open firing

and finishing with wood, is inclined to seal lids firmly in their

sockets. To prevent this, I have found it effective to baste the

inside of the gallery with a thin wash of quartz and water before

putting the lid in place. The quartz coagulates but does not fuse

and can be scraped out afterwards.

The making of a teapot, then, is quite a precision job. A

possible danger is that it becomes over-precise, giving that over-

planned, over-constructed and stark effect from which so many

commercial pots suffer. Precision of the right sort comes naturally

from the foundation of firm discipline in throwing and handling

one's tools and from the knowledge and mastery of clay and its

whims. Only when freedom superimposes itself unconsciously

upon a foundation of sound discipline and technique, so well

learned that it has become second nature-only when the potter, while remaining aware of the need for such discipline, can be

unconscious of its actual maintenance while exercising his free will

can we secure to the full those sualities of life and inevitability

which we rightly look for in hand-made pots.

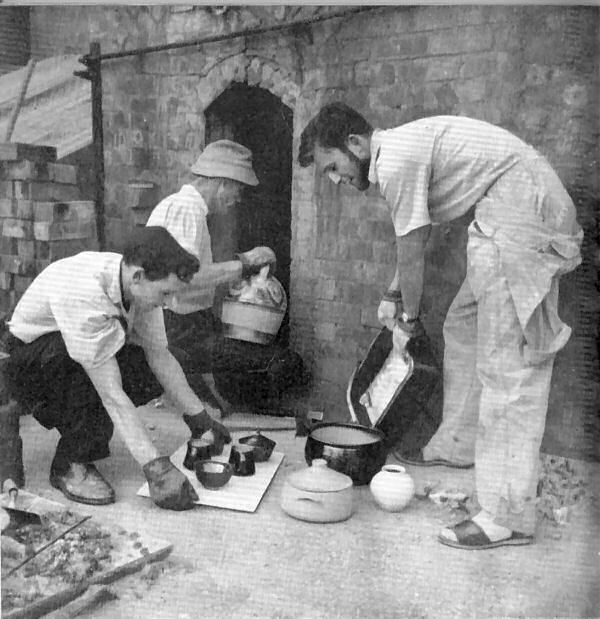

Unpacking the kiln at Avoncroft Pottery in 1958.

Geoffrey Whiting at the kiln entrance with Alan Gayden and and Michael Bailey.

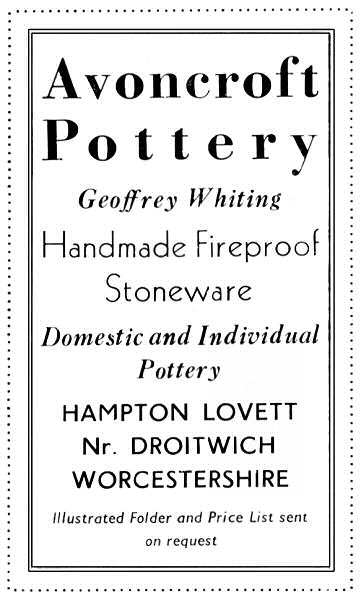

Avoncroft Pottery advert, Pottery Quarterly, Autumn 1955.

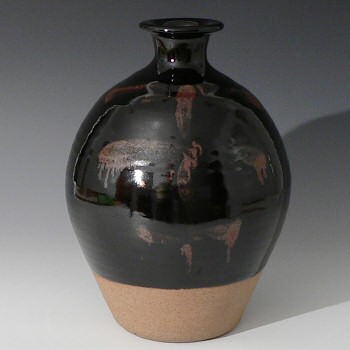

Geoffrey Whiting Pots

Teapot, 13cm tall

Wax resist charger, 31cm diameter

Large bottle vase, 32cm tall

Brush pot, 6cm tall

Fluted bottle, 17cm tall

Globular vase, 19cm tall

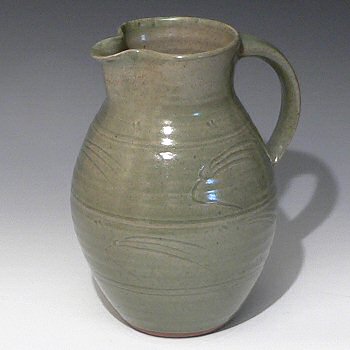

Large jug, 27cm tall

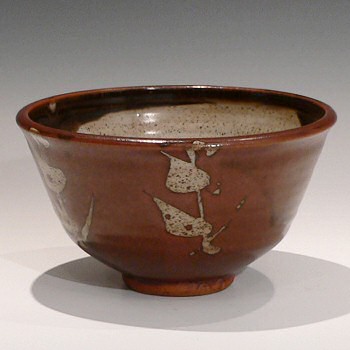

Wax resist bowl, 19cm diameter

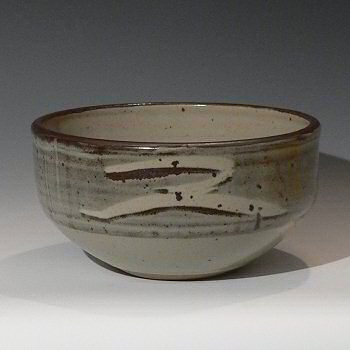

Teabowl, 7.5cm tall

Teabowl, 8cm tall

Teabowl, 7cm tall

Fruit bowl, Z pattern, 26cm diameter

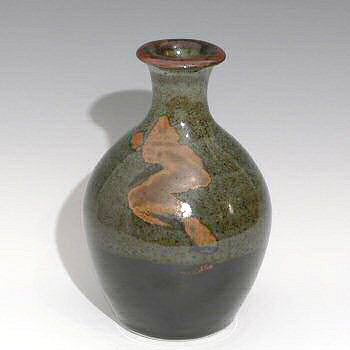

Vase, 21cm tall

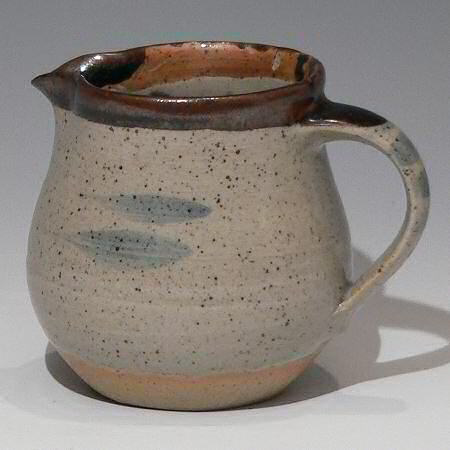

Standard ware cream jug, 11cm tall